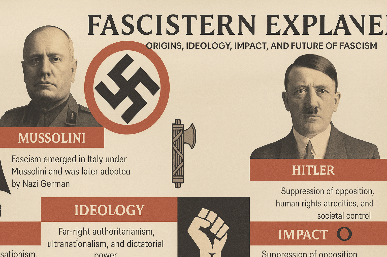

Fascisterne Explained: Origins, Ideology, Impact, and Future of Fascism

Fascisterne Explained: Origins, Ideology, Impact, and Future of Fascism

When I first came across the term Fascisterne, a Danish word that translates into English as “fascists,” I couldn’t help but notice the strong associations it draws to World War II, authoritarianism, and political extremism. Yet, there is a broader, even deeper context behind it.

Its origins in early 20th-century Europe show how the concept of fascism, those who identify with it, or are labeled under it, have evolved significantly through both modern interpretations and unexpected offshoots.

In today’s world, gaining an understanding of fascisterne requires more than just reading about history. It’s about recognizing political patterns and observing how extremist ideologies weave into the forces that shape modern societies.

This article attempts to break apart the history, trace the beliefs, explore their rise, and reflect on the ongoing relevance of fascisterne. I find that combining a clear, almost expert-informed outlook with a casual voice makes it easier for readers to follow along.

- Broader context: rooted in origins yet linked to modern interpretations

- Political patterns: repeating across societies

- Extremist ideologies: constantly evolving and shaping forces

- Relevance today: seen in both history and modern voices

What is Fascisterne?

When people talk about Fascisterne, they usually mean more than just a label. The term, often translated as “fascists,” refers to organizations, groups, and ideologies that advocate or align themselves with the principles of fascism.

This far-right, authoritarian political ideology is characterized by dictatorial power, forcible suppression of opposition, and strong, centralized control. Over time, it has been used to describe different factions and movements that promote nationalist, xenophobic, and totalitarian ideals.

Historically, fascism rose to prominence in the early 20th century, with notorious regimes in countries like Italy under Benito Mussolini and Germany under Adolf Hitler.

They promoted aggressive nationalism, militarism, and a disdain for democratic values, leading to widespread destruction, loss of life, and World War II. Even after these regimes had fallen, their ideologies continued to influence extremist groups across societies.

Today, organizations inspired by Fascisterne still aim to bring fascist ideas into modern political discourse. While they may present themselves differently, their fascist ideals echo the same patterns:

- Nationalism elevated above all

- Militarism glorified as strength

- Suppression of dissent as necessity

- Totalitarian control justified as order

The Birth of Fascisterne: Seeds of Totalitarianism

The term fascisterne first became relevant in the aftermath of World War I, when Europe was left devastated. With millions dead, empires collapsed, economies in ruins, and national pride shaken, these turbulent conditions created fertile ground for extremist ideologies to thrive.

The first Italian Fascism, spearheaded by Benito Mussolini in 1919, tapped into this chaos to build a movement that would alter history.

I’ve often reflected on how Mussolini, a former socialist turned nationalist, formed the Fasci di Combattimento, attracting war veterans, disillusioned citizens, and nationalists alike.

By 1922, Italy witnessed the infamous March on Rome, which marked his ascension to power. Italy became the first nation-state governed by an ideology that would inspire fascist-and movements across Europe.

Shortly thereafter, Germany saw Adolf Hitler emerge as the central figure of fascism’s German variant, the Nazi Party. By exploiting economic despair, national humiliation from the post-Versailles Treaty, and fueling ethnic nationalism alongside anti-communist sentiments, the Nazis tapped into the frustrations of the people to seize control in 1933.

Elsewhere, fascistine found adherents in Spain under Francisco Franco, Hungary with Miklós Horthy, Romania’s Iron Guard, and Britain’s Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists. Despite geographic differences, these movements shared common themes:

- Authoritarianism as governance

- Nationalism as identity

- Suppression of dissent as necessity

The Origins of Fascism: Where Fascisterne Came From

To understand fascisterne, we need to look back at the roots of fascism itself. The term fascism comes from the Latin word fasces, a bundle of rods bound together, symbolizing unity and power.

This ancient symbol was later appropriated by Benito Mussolini’s regime in Italy, giving a modern political movement a historical image that carried both strength and authority.

- Latin word fasces → bundle of rods

- Unity and power → core values reinterpreted

- Mussolini’s regime → appropriated symbol for politics

Italy: The Birthplace of Fascism

Fascism began in Italy after World War I, a time when the country was riddled with social unrest, economic instability, and political fragmentation. Out of this chaos, Benito Mussolini, once a socialist journalist, founded the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento in 1919, a paramilitary movement that promised to restore order, rebuild national pride, and project military strength.

By 1922, Mussolini would become Prime Minister, using a combination of political maneuvering, threats, and violence during the infamous March on Rome. From there, fascism took hold in Italy, characterized by nationalism, authoritarian leadership, anti-communism, and the suppression of dissent.

- 1919 → Fasci Italiani di Combattimento founded

- 1922 → March on Rome, Mussolini becomes Prime Minister

- Core traits → nationalism, authoritarianism, anti-communism, suppression of dissent

Germany: The Rise of Nazism

Nazism in Germany shared traits with Italian fascism, but under Adolf Hitler, the Nazi Party rose to power by exploiting economic despair, widespread resentment from the Treaty of Versailles, and fueling deep-seated antisemitism.

The Nazis incorporated fascist ideology, but added a distinctly racist and genocidal component that ultimately led to the Holocaust. Within this frame, the term fascisterne can also apply broadly—not just to Mussolini’s followers, but to Hitler’s Nazis, who are often included due to their overlapping ideologies.

- Economic despair + resentment → fertile ground for Nazism

- Antisemitism + racism → radicalized fascist ideology

- Holocaust → defining genocidal outcome

- Fascisterne → applied to both Mussolini’s and Hitler’s Nazis

Other Fascist Movements in Europe

Fascisterne, weren’t, Italian, German, phenomenon, 1930s, 1940s, fascist, movements, sprouted, Spain, Franco, Hungary, Romania, sympathizers, UK, Scandinavia, groups, seized, national, power, shared, core, beliefs, authoritarianism, nationalism, rejection, liberal, democracy

Ideological Pillars of Fascisterne

The implementations of fascisterne across Europe were varied, but each followed a similar ideological framework. These movements were marked by several foundational principles that defined how they sought to reshape societies, often combining political force with cultural manipulation.

Ultranationalism

At the heart of the fascisterne ideology was Ultranationalism, rooted in the glorification of the nation. It promotes the superiority of race, while frequently demonizing outsiders, immigrants, and minorities as existential threats. This framing not only justified internal oppression but also gave fuel to expansionist ambitions.

Authoritarianism

Authoritarianism in fascisterne movements advocated centralized and dictatorial leadership. The supreme leader was viewed not merely as a political figure, but elevated into a national symbol—someone above reproach, embodying the will of the people. From my perspective, this element often blurred the line between governance and personality cults

Militarism and Glorification of Violence

A defining pillar was Militarism and the glorification of violence. War was not simply policy but elevated to a virtue. The fascist ideology promoted a belief that strength comes through struggle, a theme that permeated fascisterne propaganda. Youth were deliberately indoctrinated to idolize soldiers, embrace warfare, and even dream of conquest as noble paths.

Anti-Communism and Anti-Liberalism

Equally significant was the rejection of opposing systems. Anti-Communism and Anti-Liberalism meant that fascisterne abhorred the democratic process and Marxist ideologies alike. Liberal democracies were painted as weak, while communist doctrines were cast as chaotic. By positioning themselves as a so-called third way, fascists gained support from capitalists, the middle class, and conservative elements of society.

Corporatism and State Control

Unlike pure capitalism or outright socialism, fascisterne rejected unregulated capitalism and class warfare. Instead, they proposed a corporatist state where business, labor, and state sectors all operated under government control for the supposed common good. On paper, this appeared balanced, but in practice it enabled rigid state control over nearly every aspect of life.

Racial Purity and Eugenics

Perhaps the darkest element was the pursuit of Racial Purity and Eugenics. Under regimes like Nazi Germany, the fascisterne ideology extended into radical racial theories. Jews, Roma, Slavs, and disabled individuals were labeled inferior and systematically targeted for elimination through official policies that culminated in genocide. This distortion of science into ideology turned prejudice into state-mandated violence.

The Societal Impact of Fascisterne Rule

Suppression of Civil Liberties

One of the first hallmarks of fascisterne rule was the suppression of civil liberties. Freedom of press, speech, and assembly quickly became early casualties. Dissenters, whether academics, journalists, clergy, or activists, were silenced, many imprisoned, some exiled, and others outright killed. This eradication of dissent created a society where fear replaced open debate.

Redefining National Identity

The redefining of national identity under fascisterne regimes involved crafting belonging through bloodlines, tradition, and myth. Education and culture were redesigned to glorify the state while simultaneously vilifying the other. I’ve seen in historical accounts how such strategies made loyalty to the regime synonymous with personal identity, leaving no room for individuality.

Economic Engineering

Through economic engineering, massive infrastructure projects like Germany’s Autobahns or Italy’s reclamation of marshlands were launched to reduce unemployment and glorify the regime. While initially successful in stimulating growth, these ventures often masked deep imbalances within the system. The surface prosperity was fragile, built on political spectacle more than sustainable economics.

Social Control and Surveillance

The machinery of social control and surveillance turned daily life into a climate of suspicion. The Gestapo, OVRA, and other secret police agencies pitted neighbor against neighbor. Through fear, public trials, and intimidation, conformity was ensured. This environment destroyed trust and created societies bound together more by coercion than by unity.

Human Rights Atrocities

Perhaps the darkest legacy of fascisterne lies in the human rights atrocities. The Holocaust, carried out by Nazi Germany, systematically murdered six million Jews and millions of others, including Roma, disabled individuals, and political dissidents. History records this as one of the most infamous genocides, underscoring how unchecked authoritarian power can lead to catastrophic loss of life.

The Fall of Fascisterne and Post-War Reckoning

The fall of fascisterne came with the post-war reckoning that followed World War II. It marked the beginning of the end as the Allied forces dismantled the regimes of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, leaving both countries devastated and divided. In many ways, the collapse of these powers revealed the fragility of totalitarianism once external pressure mounted.

Nuremberg and Justice

The Nuremberg Trials of 1945–46 became a cornerstone of justice, holding key Nazi officials accountable for war crimes and crimes against humanity. These trials established precedents in international law, particularly with regard to genocide and individual responsibility. For me, this moment stands as one of history’s first attempts to prove that leaders could not hide behind power when atrocities were committed.

De-Fascistization and Reconstruction

In the aftermath, Germany underwent a process of denazification, while Italy established a republic. Still, remnants of fascisterne ideology persisted, sometimes reemerging in subtle forms within certain sectors of society. The challenge of de-fascistization and reconstruction was not only institutional but cultural, as rebuilding trust in democracy required more than new governments.

Memory and Education

Post-war Europe invested deeply in Holocaust education, memorials, and broader cultural remembrance. The horrors of fascisterne regimes became critical elements in national narratives, ensuring future generations would recognize the dangers of authoritarianism. I’ve noticed how this emphasis on memory and education transformed into a moral compass, reminding societies of the cost of forgetting.

The Future of Fascisterne

The future of Fascisterne movements remains deeply uncertain, even as modern democracies build laws and systems to counteract extremist ideologies. The rise of populism and nationalism in certain parts of the world has given these groups new life, though their ability to grow is often tempered by societal pushback.

More people recognize the dangers of embracing divisive politics, making resistance an active part of civic life.

To prevent the spread of extremist ideologies, it is crucial that societies promote education, tolerance, and democratic values. Governments, civil society, and individuals each have important roles in combating the influence of Fascisterne by fostering environments that support inclusivity, peace, and respect for human rights.

From my experience observing modern discourse, it’s often at the grassroots level where change begins—small actions that build resilience against extremist narratives.

- Populism + nationalism → fuels divisive growth

- Societal pushback → key in halting expansion

- Education + tolerance → tools to resist extremist ideas

- Human rights + inclusivity → values that strengthen democracy

Conclusion

The story of fascisterne is more than a chapter in a history book, it is a cautionary tale of what happens when hate, fear, and unchecked power collide.

The legacy of fascism continues to echo in today’s political discourse, reminding us why it is important to understand its roots and recognize modern disguises.

By exploring the ideology, rise, and aftermath of fascisterne, we equip ourselves with knowledge to protect democracy, uphold human rights, and ensure history does not repeat. Though the world has changed since Mussolini and Hitler, the danger of authoritarianism remains, and with it, our responsibility to stand against such threats.

- Cautionary tale → unchecked power and fear

- Legacy → fascism echoes into the present

- Knowledge → tool to protect democracy and human rights

- Responsibility → remain vigilant against authoritarianism

Faqs

What does fascism actually mean?

At its core, fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology. It was a movement that rose to prominence in early-20th-century Europe, combining extreme nationalism with centralized dictatorial control. When I first studied this period, what struck me most was how quickly such systems could dismantle democratic traditions.

Which country is known as fascism?

The first fascist country was Italy, ruled by Benito Mussolini, often called Il Duce. The Italian Fascists imposed totalitarian rule, crushed political and intellectual opposition, and emphasized economic modernization, traditional social values, and even a rapprochement with the Roman Catholic Church. Italy’s example became the model that inspired other regimes across Europe.

Is fascism closer to capitalism or socialism?

Historian Jürgen Kuczynski characterizes the fascist economy as a type of monopoly capitalism. It preserves fundamental traits of capitalist production, including the fact that production is carried out for the market by privately owned firms that employ workers for a wage. Unlike socialism, it does not seek equality, but unlike free capitalism, it thrives under heavy state direction.

What is the color of fascism?

In Italy, black became the official colour of fascism, as it was tied to the National Fascist Party. As a result, modern Italian parties generally avoid it as a political colour, but historically it was customary to identify neo-fascist groups like the Italian Social Movement with black. The symbolism of color in politics still fascinates me—it shapes perception as much as ideology itself.

What is the opposite of fascism?

The opposite of fascism is often framed as counterrevolutionary anti-fascism. This includes both conservative and liberal anti-fascism, which refers to opposition grounded in the defense of democracy, constitutional order, and traditional institutions. In practice, it means protecting freedoms and building resilience against authoritarian threats.

8zggap

I cling on to listening to the news talk about getting free online grant applications so I have been looking around for the best site to get one. Could you tell me please, where could i get some?

What’s Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It absolutely helpful and it has aided me out loads. I hope to contribute & assist other users like its aided me. Great job.

2cqur3